The annexation of East Belgium by Germany (1940) was against international law, yet during the war, the Belgian state had not reacted to the annexation, neither by protesting against it nor by recognition. In the meantime, 8,800 East Belgian men fought for the German Wehrmacht. Of these, 800 had volunteered. The remaining 8,000 were drafted, like all German men fit for service. The citizens of the disctricts of Eupen and Malmedy had been full citizens of the ‘Third Reich’, with all the rights and duties that entailed since 1941.

-

![Michel_Pauly]()

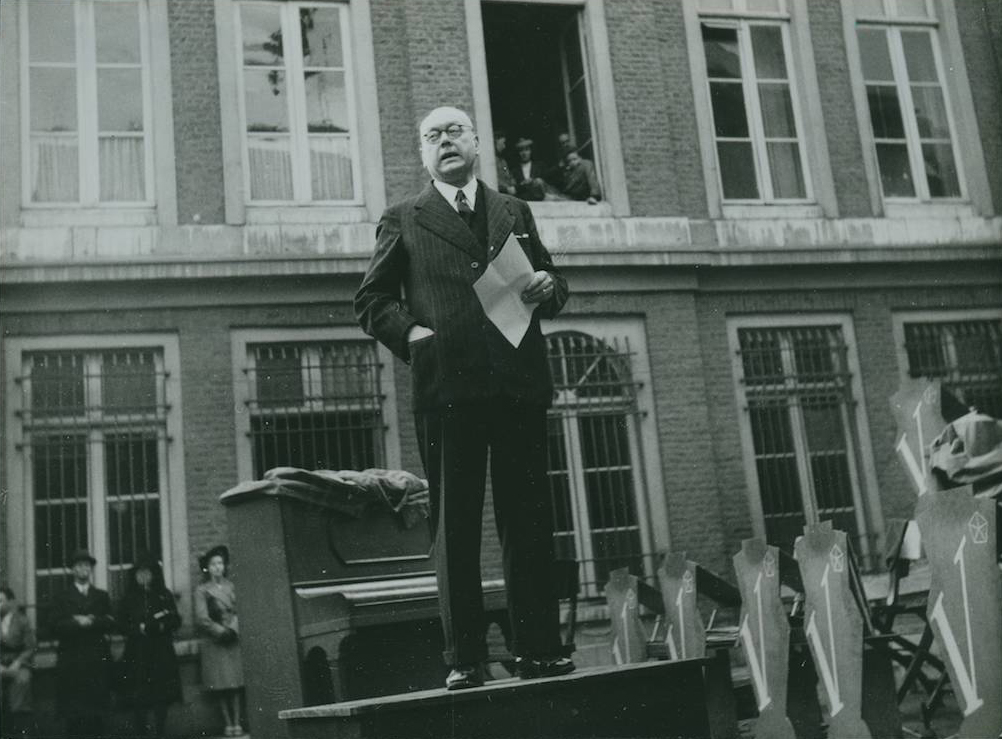

Michel Pauly

Opinion:

On cultural debates on remembrance in Luxembourg:

‘Such debates still exist today in Luxembourg [...]. A political landslide was triggered in this debate when the Luxembourg historian Vincent Artuso published his report on the collaboration of the Luxembourg administration under Nazi rule in 2015. One of his results [...] was that the Luxembourg administration had actively collaborated with the Nazis, including the persecution of Jews. This led to the Luxembourgish Prime Minister publicly apologising to the country’s Jewish community for the misdemeanours of the Luxembourg state during the Second World War. The ‘Artuso Rapport’ raised old questions that had been hushed up, and it showed that the events of the Second World War in Luxembourg are still far from having been dealt with.’

After the war, the government sought to judge East Belgians by the same standards as all Belgians, even though the living conditions between the annexed border area and occupied Belgium had been quite different. This led to the so-called purge.

The term stands for a veritable purge hysteria that arose in Belgium from the summer of 1944 onwards. At first, these were essentially well-intentioned efforts to denazify and punish collaborators. However, ‘purge’ and ‘denazification’ are not synonyms. Why?

Some facts: When the war was over, many East Belgian soldiers were first taken prisoners of war and, after their release, sent to Belgian prisons. In 1946, around 63,000 people lived in East Belgium. 6,000 to 7,000 citizens were interned, around 18,000 court cases were opened, 3,201 citizens were charged. 1,503 East Belgians were convicted. Thousands were temporarily deprived of their civil rights. In 1946, almost 50 per cent of the electorate was excluded from the polls. 461 people were stripped of their Belgian citizenship.

-

![Claudia Kühnen_Aachen]()

Claudia Kühnen

Opinion:

On commemorating the German denazification:

‘In fact, this did not become an issue in German society until the 1960s [...]. The consensus among most people today is that denazification did not succeed – many high-ranking representatives of the state, such as judges and the like, were reinstated after the war and have never been punished for their deeds. The fact that many scientists and doctors were recruited by the US and did not receive punishment likewise contributes to this impression. Such issues of just punishment and the question of guilt, however, still remain today.’

Without a doubt, those who had clearly declared their support for National Socialism and had violated universal rights, such as human rights, had to be punished. But an entire population was placed under general suspicion because, as citizens of the ‘Third Reich’, they had not lived according to the laws applying to occupied Belgium.

In the culture of remembrance, people once again felt like victims. A more nuanced examination of this chapter of history failed to materialise, and the purge remained a taboo subject until the 1990s.

-

![Adeline_Moons]()

Adeline Moons -

Jeroen Petit

Opinion:

‘This discussion certainly existed in Flanders after the Second World War. After the war, there was likewise a movement advocating for amnesty for collaborators. In 1961, a provision was also made that collaborators could be rehabilitated under certain circumstances. However, intensive discussions about the appropriateness or inappropriateness of collaboration were only held in back rooms. Public discussion was impossible. One reason for this was the emotional load of the debates; among other things, the Holocaust has not yet been dealt with in Belgium. Also, the discussion is often exclusively about the Flemish Movement. There is often little room for other aspects of collaboration in Flanders. Collaboration in Flanders was much more than just military collaboration. There was also economic collaboration. The role of Flemish women and children of German Wehrmacht soldiers also plays a role. Many of these people were lumped together during the various waves of purging after the Second World War.’