1975 Irene Janetzky received the German Federball Cross of Merit (Source: BRF sound archive, 11 January 1975).

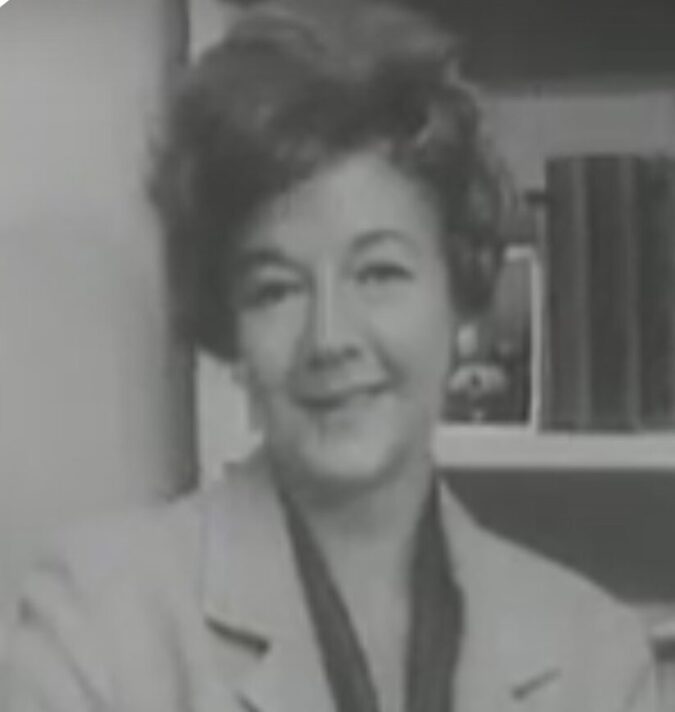

Irene Janetzky (* 13 May 1914 in Duisburg; † 19 July 2005 in Brussels) was the woman who almost single-handedly laid the foundations of today’s Belgian Broadcasting Corporation. Yet she has received very little attention in the historiography of East Belgium. This is probably due to the fact that she was present in East Belgium mainly through her voice.

Since 1945, Janetzky had influenced the destiny of the ‘Émissions en langue allemande’ (German language broadcasts). The woman at the head of the German broadcasts was the daughter of a harbour engineer. The name Janetzky stems from the Silesian origin of her father, who came from Ratibor (now Racibórz, Poland). Her mother was from Bingen on the Rhine. Shortly after Irene was born, her father died on the Western Front in September 1914. Her widowed mother then met Bernhard Willems, now known as an important historian of East Belgium. At the time, Willems was a teacher at the secondary school in Malmedy. After the Treaty of Versailles was applied in Eupen-Malmedy-Sankt Vith, the family took Belgian citizenship. Irene Janetzky spent her youth in the Malmedy area, attending the Royal Athenaeum (secondary school) there before going on a study trip to England and Italy in the 1930s to improve her language skills. Bernhard Willems did much to broaden his stepdaughter’s horizons.

The contact between the Institut National de Radiodiffusion (INR), the national radio institute, and Janetzky came about by chance. During the Second World War, the Reich Health Office of the Nazi regime was housed in the house of Bernhard Willems in Malmedy. This house was made available by Willems to the Belgian authorities after the Second World War, and he was in contact with them. From then on, he worked to find new sources of information for German-speaking Belgians.

In this context, there is a letter in which Janetzky is asked to broadcast in German for an unspecified period of time. It is noteworthy that the letter is not addressed to Janetzky, but to her stepfather Willems. The letter was accompanied by a contract signed by Theo Fleischmann, a pioneer of Belgian radio in the inter-war period. Interestingly, the contract was signed on 4 October 1945, three days after the first broadcast in German. It did not guarantee any rights for the future (‘[…] engagement ne […] donne aucun droit quelconque pour l’avenir.’) and made it clear how precarious the station was for German-speaking Belgians in its early years.

Janetzky can certainly be called a pioneer of Belgian broadcasting. As one of the INR’s first announcers, she set the tone for the Belgian authorities in their dealings with German-speaking citizens. Because of her linguistic skills, Janetzky presented the first edition of the Eurovision de la Chanson on Belgian television. She also accompanied several Belgian delegations on their trips abroad, including to the United States.

Janetzky’s private archives show that she had a network throughout Belgium. The documents also contain traces of media contacts throughout Europe. They show whom Janetzky met on various trips and in which organisations she was able to establish contacts. One name that appears here and there in Belgian politics is the family name Nothomb. Several letters suggest that there must have been personal links between the Janetzky family and various members of the Nothomb family. The RTB archives at the General State Archives also show that Pierre Nothomb in particular – who was in favour of Eupen-Malmedy becoming part of Belgium after the First World War – kept a close eye on developments at the East Belgian station.

As mentioned above, it paved the way for German-language broadcasts for a long time. Among other things – and this again illustrates her contacts with other public broadcasters – she was a co-founder of the ‘Ring deutschsprachiger Sendungen’ (network of programmes in German language). This was an organisation designed to facilitate the exchange of German-language programmes between public broadcasters. The minutes of the meetings show that Janetzky tried to strengthen cooperation between the institutions, but without a sufficient budget she could neither provide nor pay for any content. They, and therefore Belgian Radio, were dependent on the goodwill of the other public broadcasters.

Janetzky was also a member of the International Association of Women in Radio and Television, an international association of women for women. The aim was to unite women in the media world, to promote the reconstruction of Europe and to build cross-border networks. The members of the association were mainly pioneering women in radio and television, most of whom created informative and educational programmes for women.

Although Belgian Radio, under Janetzky’s direction, was mainly a mouthpiece for Brussels in the direction of East Belgium, and she worked to integrate the German-speaking Belgians, especially by means of ‘Belgian’ themes, Janetzky did not have a clear tendency towards any political party. However, she was rather liberal, ‘libéralisante’. She tried to stay above politics for a simple reason: Janetzky believed that political actors would destroy ‘her’ programmes. Within the BHF, she tried to maintain a political balance by insisting on objective reporting. Nevertheless, Janetzky also saw herself as one of the initiators of cultural autonomy in Belgium, but was dissatisfied with the form that it took.

Janetzky did not directly take sides in the autonomy debate. Nor did she stifle the debate by enforcing the public broadcasters’ rules of objectivity with an iron hand. Rather, she favoured the kind of freer reporting that her young presenters and radio journalists were doing at the end of the 1960s. She tended to defend her staff and had a rather broad view of freedom of the press. For example, although she aspired to ensure stronger ties between the Kingdom of Belgium and the German-speaking Belgians, she in no way suppressed her staff’s reporting on the autonomy of East Belgium.

She received several awards for her work. These included the German Federal Cross of Merit, First Class, in 1975, the Grand Silver Medal of Honour for Services to the Republic of Austria in 1973, and the Order of Polonia Restituta in 1965. She was also made Chevalier (1964) and Officier (1968) of the Order of Leopold.

In 1974, after 29 years of service, she retired as Director of the BHF.

Quellen und weiterführende Literatur

Vitus Sproten, Ostbelgien hört Ostbelgien. Der Belgische Hörfunk im Kontext der Debatten um die Kulturautonomie der deutschsprachigen Belgier 1965-1974, Brussels 2019.