As in Alsace-Lorraine, a transitional regime was to prepare the integration of the former Prussian districts of Eupen and Malmedy – today’s East Belgium – between 1920 and 1925. The High Commissioner Herman Baltia, who headed this regional transition-government, was directly subordinate to the Belgian Prime Minister and had far-reaching powers.

-

![Adeline_Moons]()

Adeline Moons -

Jeroen Petit

Meinung:

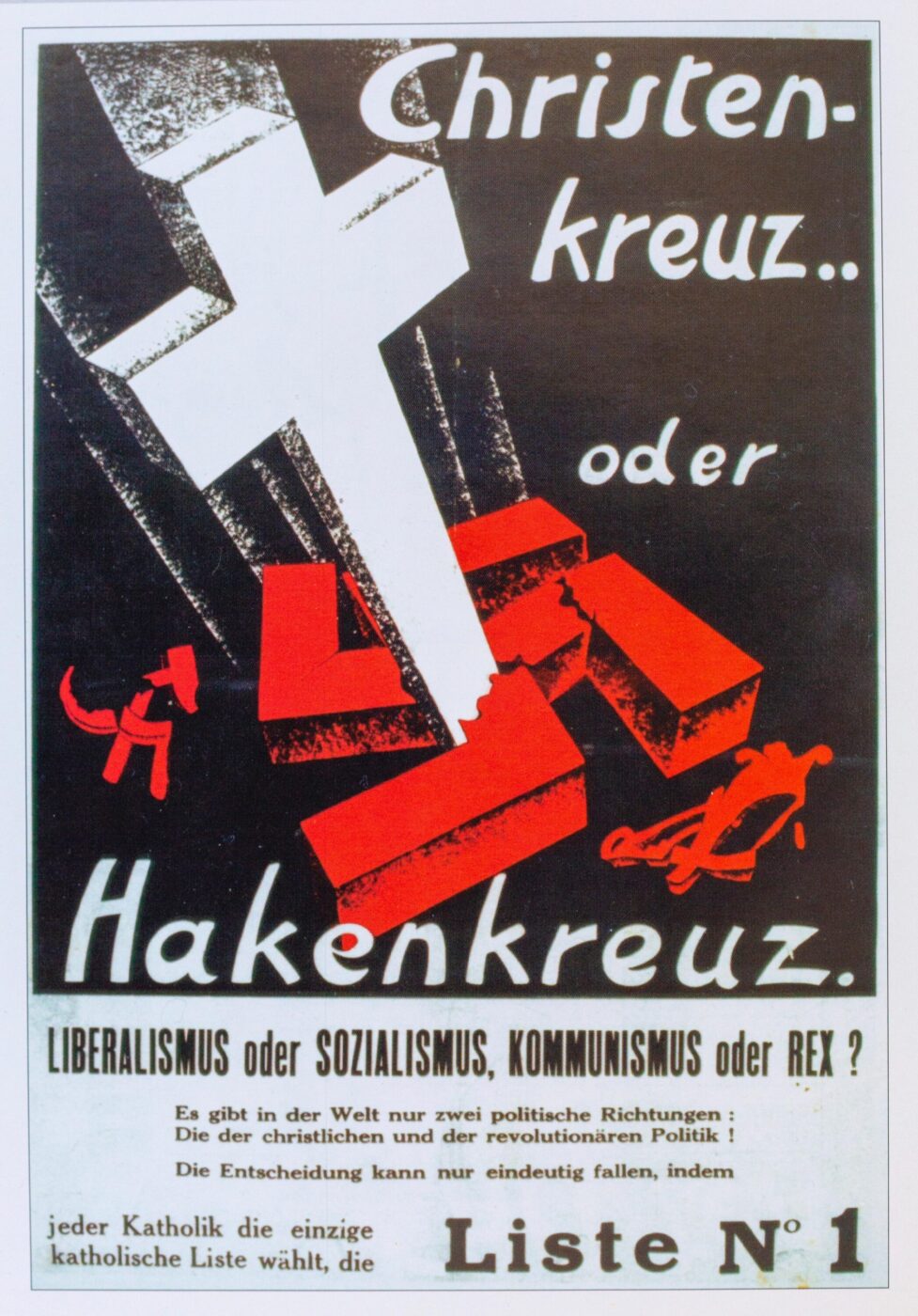

‘There were similar tendencies in Flanders and Belgium after the separation from the United Kingdom of the Netherlands. There were – and still are today – people who are in favour of reuniting Flanders, or the whole of Belgium, with the Netherlands in order to form ‘Dietsland’. These people are called ‘Dietslanders’. In Flanders, however, these people were only a small minority. In East Belgium, far more people were in favour of affiliation with Germany. Probably in every area of land that has once been part of another country, there are people who think back nostalgically to their former rulers.’