In 1945, the Eifel and Ardennes were devastated and the Eupen region was in a state of frozen shock. The transition between wartime and peacetime was not easy. Why?

Domestically, the post-war years were marked by an urge for justice and revenge. After four years of occupation, collaborators were about to be brought to justice, and spies and traitors about to be judged. Everything reminding people of the loathed occupier was supposed to be eradicated. National Socialism, German nationalism, but also German language and culture were often put on the same level. The well-intentioned efforts of denazification and the punishment of collaborators became anchored in the collective consciousness under the catchwords ‘répression’ (criminal prosecution) and ‘épuration’ (purge). From August 1944 on, a veritable hysteria of purges arose in Belgium, directed mainly against collaborators. This was also the case in France, Czechoslovakia, Poland, and many other European countries.

It also began in East Belgium, with its population of around 60,000, in September 1944 and only slowly subsided in the 1950s. During this period, the Belgian resistance – the so-called White Army – and the military prosecutors in the cantons of Eupen, Malmedy, and Sankt Vith imprisoned at least 6,000 to 7,000 citizens in internment camps or prisons. For the approximately 60,000 inhabitants of East Belgium, 18,427 legal investigations were opened. Charges were brought in 3,201 of those cases, and ultimately 1,503 citizens were convicted. This was four times the Belgian average. Around 10,000 citizens – their relatives being included in this number – were supposed to be stripped of their Belgian citizenship and deported to Germany in 1946. Yet, in the end, the Belgian state respected to a certain extent the particular situation in East Belgium, and only 461 citizens were affected by this special measure.

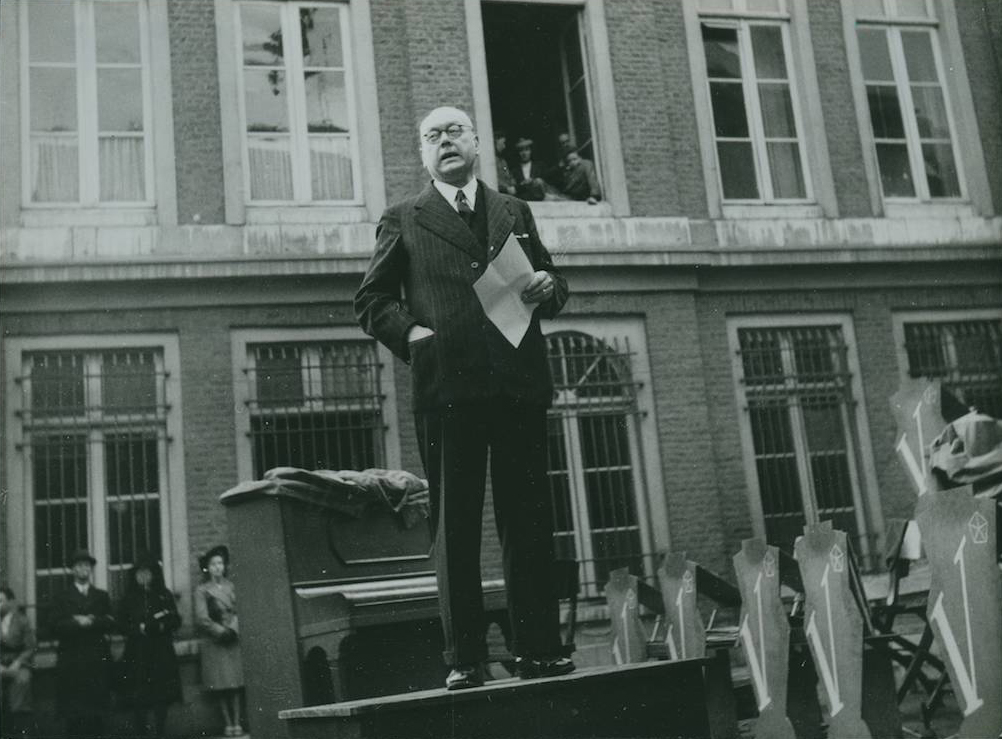

Many East Belgians were deprived of their civil rights in whole or in part, for a limited or unlimited period. In 1946, for example, about 50 per cent of men in East Belgium were excluded from the polls (women were not given the right to vote until 1948). By June 1946, presumably well over 4,000 citizens were largely excluded from social life by a negative civic certificates. The same procedure was followed in enterprises, administrations, associations, and so on. Since countless files had been destroyed or carried off by the White Army, and the military courts lacked corresponding evidence, the mayor of Eupen, Hugo Zimmermann, called for widespread denunciation.

Special treatment hardly seemed possible against the background of the domestic tensions surrounding the purge. Therefore, the civilian population of East Belgium as well as the 8,700 Wehrmacht soldiers from the region were set to be judged, for the time being, along the same standards as the inhabitants of occupied Belgium. In the immediate post-war period, it was almost impossible to take into account the special role of East Belgium.

On the one hand, the Belgian authorities needed a long time to be able to reconstruct the everyday life of the East Belgians in the ‘Third Reich’ from 1940 to 1944. On the other hand, the military courts complained that they had numerous charges against possible collaborators before them, but that the Belgian resistance had destroyed or concealed files in the region on such a massive scale that there was hardly any legal basis for a conviction.

The majority of the population felt that the purge was unjust. The justification used almost everywhere was that East Belgium had been annexed, and not occupied. In the first phase, numerous, some harsh sentences were passed, most of which were mitigated or completely overturned in the appeal proceedings.

The post-war policy for East Belgium, developed in Brussels and in the attached district commissariat of, is of particular interest, as is the attitude of the population. The plans included the borders with Germany to be largely closed and the people to be oriented towards the interior of Belgium. Furthermore, the authorities sought to promote an exaggerated Belgian nationalism, including enforced use of French language in schools and administrations. In this context, many East Belgians self-assimilated, preferring the French language and avoiding conspicuous devotion to German culture. As a result, the German language gradually disappeared from the Malmedy area.

For the Belgian Eifel, however, the years after the war were important for another reason. The material reconstruction of the destroyed villages took place during this time. This lasted until the 1960s. While the communities in the interior of Belgium were spared major destruction during the war, the situation was different in the east of Belgium. In this situation, some inner-Belgian communities took on sponsorships for villages in eastern Belgium and alleviated the greatest need by donating food and materials.

The purge remained a taboo subject in the region until the end of the 1990s. Emotionally, everyone had experienced and processed the time differently. People had actively kept quiet about the time and retreated into a role as victims: they saw themselves as victims of the war through the annexation, through the conscription of soldiers into the Wehrmacht, or as victims of the Battle of the Bulge, and as victims of the purge. Only after the archives were opened did the first works appear that scientifically investigated and presented the topic. To this day, the question remains why the purge failed in its basic intention of establishing justice, but was apparently successful in pacifying the population.

This example shows: In this extraordinary situation, it was incredibly difficult for the courts to dispense justice in such a way that it was also perceived as just by the majority of those affected. It was also difficult for the citizens to justly classify the actions of their fellow citizens. Is that why this period was hushed up?

Today, people are quick to judge others on the internet. In social media, people are (anonymously) insulted or bullied. In court, however, judgements are always based on comprehensible facts or at least circumstantial evidence. What information is needed in everyday life to form an opinion and permit judgement?