-

Since 11 November 1918, following the armistice, the German army moved through Belgium and also through the German districts of Eupen and Malmedy, back into the Reich – as losers. Yet, they were not necessarily received as such at home. The defeated German army was followed by British, French, and later Belgian troops, who occupied the districts of Eupen and Malmedy and large parts of the Rhineland.

Since about 1916, voices of nationalists had been raised in both Germany and Belgium, who planned extensive annexations in the event of victory. While Germany toyed with the idea of annexing large parts of the occupied neighbouring countries, the Belgian politician Pierre Nothomb founded the ‘Comité de Politique nationale’ (CPN) at the end of 1918, which sought territorial cessions in favour of Belgium: the Scheldt estuary as well as the province of Limburg at the expense of the Netherlands, the entire Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, as well as parts of the Rhineland with an access to the Rhine near Duisburg. As early as 1916, Nothomb had outlined the scope of these annexations in his book ‘La barrière belge’. He justified the claim to the districts of Eupen, Malmedy, Schleiden, Monschau, and Bitburg historically: because these areas had belonged to the Austrian Netherlands and the young Belgian state founded in 1830 had been the legal successor to this state, these areas had always been Belgian. This error, according to Pierre Nothomb, must therefore be corrected.

However, different views competed in the discussions on a possible peace treaty: notably nationalist politicians across Europe wanted a peace that imposed extensive annexations and high reparations on the loser. American President Woodrow Wilson, on the other hand, had introduced the principle of the peoples’ right to self-determination. According to this principle, each nation should be allowed to determine its own fate. In this way, Wilson took into account the democratisation of many European societies. Above all, the minority problems in the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, which disintegrated in October 1918, needed solving.

From 18 January 1919 on, the victorious powers met in Versailles to discuss a peace treaty. Belgium was unable to push through its desire for far-reaching annexation. The Treaty of Versailles, which was signed on 28 June 1919 and came into force on 10 January 1920, would finally only provide for the annexation of Prussian and Neutral Moresnet as well as the districts of Eupen and Malmedy.

For both Belgium and France, this region was of strategic importance to ward off a renewed attack by Germany. In a sense, the area was considered the vanguard of the Liège ring of fortifications and was the first low mountain range between the Rhine and the more westerly areas.

The area was rich in forests and water. The abundance of forests was meant to generate long-term revenue and to provide reparation for the damage caused by the German army. The low-lime water was considered an important raw material for the textile industry in Verviers.

Some territorial cessions of the German Empire came into force immediately. In other regions, a free, secret referendum organised by a neutral power was held. The mode laid down in the Treaty of Versailles for the districts of Eupen and Malmedywas, however, unique. Here, a so-called ‘public expression of opinion’ (in the original English text) was to be held. This alone allowed for protest votes in public lists that were displayed in the district towns of Eupen and Malmedy. The Belgian authorities were responsible for organising this referendum.

The Belgian authorities thus organised the referendum in such a way that the cession of the two counties to Belgium was very likely. Hence, it became known as the ‘petite farce belge’, a farce, even in political circles in Brussels, and perceived as an injustice in Eupen, Malmedy, Sankt Vith, and Germany. As a result, by 23 July 1920, only 271 people had entered their names on the lists, and the League of Nations finally approved the change of state of the two districts on 20 September 1920.

It is questionable whether this vote reflected the will of the people.

First, a look back: in 1825, Prussia introduced compulsory education. One hundred years later, the majority of the population was literate. Since the end of the 19th century, a growing minority of households, even in rural areas, had a subscription to a newspaper, enabling them to participate in the political. The same period also saw the emergence of numerous associations and interest groups. As proto-democratic institutions at the lowest level, they strengthened the demand for participation in society and politics. Pre-democratic processes developed through local council elections and Reichstag elections. In 1920, the majority of the people of Eupen-Malmedy probably expected to have a say in their fate – in stark contrast to 1815.

Previous historical work shows that both Belgium and Germany went to considerable lengths in terms of financial and propagandistic effort in the run-up and during the ‘public expression of opinion’. There were petitions, protests, and strikes among the population. Meanwhile, historians agree that the general public, however, adopted a passive, wait-and-see attitude. For many, the priority was simply to stay where they were, regardless of whether this was in Germany or in Belgium.

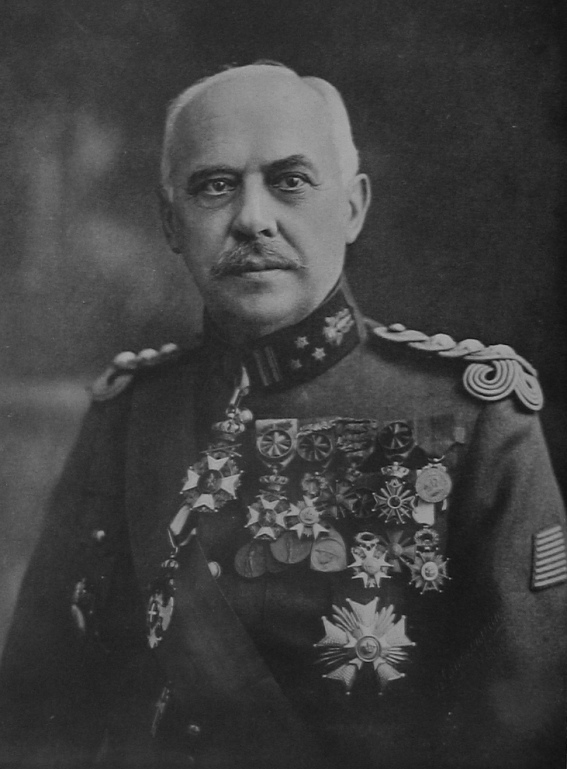

On 10 January 1920, Prussian and Neutral Moresnet were directly ceded to Belgium. The districts of Eupen and Malmedy were henceforth subordinated to a special regime under Lieutenant General Hermann Baron Baltia. He was subordinate to the Prime Minister alone and had both legislative and executive powers. Thanks to these almost dictatorial powers, he was also able to restrict the freedom of the press until the final incorporation of the freshly formed administrative units, the cantons of Eupen, Malmedy and Sankt Vith. In retrospect, his policy is regarded by researchers as moderate and quite considerate towards the new Belgians.

In communicative memory in Eupen-Malmedy-Sankt Vith, this ‘public expression of opinion’ took up a lot of space in the coming decades and overshadowed the memories of the First World War. While one part of the population got used to the idea of being Belgian and even saw advantages, another part continued to view the survey as unjust and undemocratic. This became the starting point for political and social tensions shaping the following decades. Hence, this defining period has been researched and described intensively by historians.

Today, there are influential political opinion groups in Scotland, Catalonia, and Flanders seeking independence. They denounce the previous rules of coexistence in their countries and also attempt to shift borders or create new ones. To what extent does this make sense? How could the rights of all citizens be respected in a just referendum with a close result? How can a constitutional state respond to these extraordinary questions?

-

Treaty of Versailles

Belgian school system

Eupen-Malmedy Governorate

Governorate of Eupen-Malmedy under General H. Baltia (10/01/1920-01/06/1925)

Progymnasium grammar school (Athenaeum) in Malmedy

Popular consultation

Popular consultation (26/01-23/07/1920)

Diocese Eupen-Malmedy

Folklore association Eupen-Malmedy-Saint Vith

An association for folklore in Eupen-Malmedy-Saint Vith is founded in Malmedy

First parliamentary elections

Eupen-Malmedy residents take part in Belgian parliamentary elections

Heimatbund (fatherland association)

-

-

![O Connell]() Vincent O’Connell

Vincent O’ConnellThe Annexation of Eupen-Malmedy. Becoming Belgian, 1919-1929.

New York 2019.

-

![Zoom Umschlag]() Christoph Brüll (ed.)

Christoph Brüll (ed.)Zoom 1920-2010.

Nachbarschaften neun Jahrzehnte nach Versailles, Eupen 2012.

-

![Doepgen]() Heinz Doepgen

Heinz DoepgenDie Abtretung des Gebietes von Eupen-Malmedy an Belgien im Jahr 1920.

Rheinisches Archiv, vol. 60, Bonn 1966.

-

![pabst]() Klaus Pabst

Klaus PabstEupen-Malmedy in der belgischen Regierungs- und Parteienpolitik (1914-1940).

Zeitschrift des Aachener Geschichtsvereins; vol. 76, Aachen 1965.

-

1919-1925

The Governorate

Under what circumstances can or should an area change states? Are there clear guidelines for this? What is the significance of the historical context? At a time when new wars are being sparked, the question is still relevant in the 21stcentury. The following chapter addresses in what context and under what circumstances the inhabitants of the districts of Eupen and Malmedy became part of the Belgian state in 1920, and why this transition was not always easy.