Societies in Western European countries changed fundamentally in the 1970s: the Catholic Church, membership in political organisations and traditional professions, the role of women in society or the composition of the family according to classical patterns played a different role, compared to what they had been before. Simultaneously, questions of self-realisation, peace, nature conservation, or aspects of cultural participation asuumed a new, more important role. Societies oscillated between common problems and goals (unemployment, wealth preservation, an end to certainty …) and new ‘me-time’ (self-realisation, individualism …).

Belgium played a special role in this development. The state was in crisis. The following questions arose: how should the Belgian state develop further so that the conflicts between the large linguistic groups of Flemings and Walloons could be resolved? How should participation and autonomy be shaped for the two large language groups, as well as for Brussels?

In East Belgium, the rural, Catholic-conservative society was adapting at an ever-increasing pace to the changes of the time, too. Through mobility and new means of communication, East Belgium was more closely intertwined than ever with the neighbouring regions. The basic political question was quite similar to that in the other parts of Belgium: what place should the German-speaking Belgians have in the changing Belgian state, and what form should their political participation take?

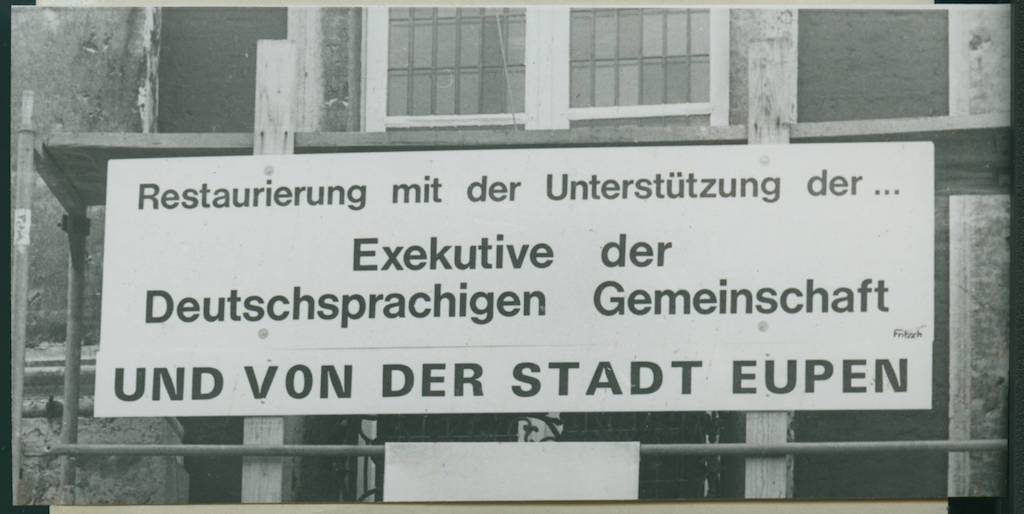

On 23 October 1973, the Council of the German Cultural Community (Rat der deutschen Kulturgemeinschaft, RdK) was established. It was comprised of 25 members who were directly elected from 1974 onwards. The RdK had few powers and budgetary resources until the establishment of the Council of the German-speaking Community (Rat der Deutschsprachigen Gemeinschaft, RDG) in 1983. However, it quickly developed into an important platform for discussion. This is where the future of the area and its largely German-speaking inhabitants was considered, debated, and also fiercely argued about. The council thus acquired high symbolic significance.

The fundamental discussions in East Belgium ran between two poles: Should the German-speaking Belgians, as a self-confident minority and linguistic group with equal rights, demand the maximum, in a federalist spirit? Or should they be restrained in shaping the new structures, demanding only elementary cultural rights and accepting the primary role of the French language and superior institutions in certain areas?

The traditional East Belgian parties (CSP, PFF, SP, Socialist Party) opted for a policy of small steps in the 1970s. Their aim was to secure the elementary cultural rights of German-speaking Belgians, in line with their inner-Belgian mother parties. They did not necessarily pursue the goal of equal rights with the other cultural communities. On the one hand, they doubted that such a small minority could have the same rights as the majority; on the other hand, an unequivocal commitment to German culture was still considered historically hostile to Belgium. These parties argued that the fate of the minority depended largely on the attitude of the national mother parties in Brussels. In retrospect, the behaviour of these parties can be described as ‘collective hesitation’.

The PDB (1971-2009), on the other hand, saw itself as the ‘driving force’ for autonomy of the German-speaking minority on an equal footing with the other two major language groups. It was linked to Belgian national politics through the Volksunie (1954-2001), a Flemish nationalist regional party. Its model was the South Tyrolean People’s Party. The latter won extensive autonomy in Italy because it succeeded in becoming the political representative of the overwhelming majority of South Tyroleans., It achieved this by constructively demanding autonomy and in being recognised as the mouthpiece of the minority. Through autonomy with equal rights, the PDB hoped for social advancement for broad sections of East Belgian society and economic perspectives for the structurally weak region.

The changing history and the different historical experiences overshadowed the political debates:

-

The PDB’s clear commitment to German culture and to the minority role in the Belgian state subjected the party to claims of being a fifth column by the traditional parties. There were fears that in the long term the PDB was working for separation from Belgium. This fear was also used rhetorically to discredit the political opponent.

-

For the traditional parties, a conformist attitude was considered proof of loyalty to the Belgian state. The PDB, in turn, discredited this attitude as ‘hurrah patriotism’. With this, the party sought to create the impression that the political opponent was an sheep-like appendix of the Walloon parties who did not defend the true interests of the minority.

The political circles in Brussels could only perceive disunity among the East Belgian parties about possible visions for the future. Only selectively did the parties in the RdK manage to formulate a common goal. This is probably why, until the turn of the millennium, the implementation of the individual state reforms in East Belgium took place months or years later than in Flanders and Wallonia.

Further major debates about this minority’s confrontation with its self-image were triggered in 1987 by the so-called Niermann affair. The regional party PDB and cultural organisations close to it had accepted money from the German Hermann Niermann Foundation. At times, the foundation’s board of trustees included members with right-wing extremist backgrounds. On the one hand, the PDB’s political opponents accused it of having accepted money from a German foundation and thus of having continued the German policy of the interwar period; on the other hand, they believed their prejudices to have been confirmed, namely that the party was anti-Belgian and still flirted with a return to Germany. The PDB denied this time and again. It admitted that this association had been a mistake and referred to the active role of two of its members in ousting the right-wing nationalist trustees.

The discussions on a bank holiday/community holiday for the German-speaking Community and its coat of arms (1990) also testified to the contradictory self-image of the elected representatives: in the case of the coat of arms, reference was made not to the region’s recent history, but to its affiliation to the Duchies of Luxembourg and Limburg in the early modern period. For the community holiday, the representatives chose the holiday of the Belgian royal house (15 November). Through such symbolism, the politicians avoided a confrontation with their own history.

Meanwhile, Belgium was reshaped by further state reforms. In 1980, the regions were established. They are responsible for economic policies. During this second state reform, no separate region was created for German-speaking East Belgium; instead, East Belgium was integrated into the Walloon Region from the beginning. This situation had supporters, but also vehement opponents. Many German speakers were afraid that, as part of the Walloon Region, they would then also become part of the French-speaking region, although the majority of East Belgians speak French well as a second language, and the status of the German language was not called into question.

The RdK, established in 1973, could only issue decrees, but no laws. Only the French and Flemish cultural councils had this power. This changed in 1984 through the establishment of the Council of the German-speaking Community (Rat der Deutschsprachigen Gemeinschaft, RDG). The second state reform also made it possible to transfer regional powers to the Community by mutual agreement. In 1989, the Communities became responsible for education. Now the Community’s budget (converted) grew from 30 to over 80 million euros.

All this shows: Through these processes, East Belgians became increasingly responsible for the political organisation of their territory. Through progressive federalisation, cultural autonomy became part of the reality of life for Eastern Belgians.

The year 1993 was the symbolic culmination of Belgian state reforms. Since the fourth state reform, the Kingdom has had the following first article of the constitution: ‘Belgium is a federal state. It is made up of the Communities and Regions.’

All this took place against the background of a changing Europe: as in the rest of Europe, the Green Movement found its place in the political landscape of East Belgium with the Ecolo party (from 1981). The Maastricht Treaty (1993) and the Schengen Agreement (1995) were further important steps towards European integration. These particularly affected the German-speaking Belgians as a border population. They saw their everyday life or leisure simplified in many ways by these developments.

The history of East Belgium between the establishment of the RdK and the federalisation of Belgium is still largely unexplored. This has mainly to do with a certain backlog of historical research in the field of the interwar and wartime periods. After initial hesitation, the period 1914-1950 was for a long time the all-dominant topic of historical research. From the 2000s on, historical research then also began to take a greater interest in the place of East Belgium in the current political structure of Belgium.

The period from 1973 to 1993 was a turbulent time. The foundations of our modern, individualistic society are rooted in it. Self-discovery is important in all our daily lives. Did these controversial discussions bring East Belgium forward or did they stand in the way of a new self-image?